Tech in Emergency Management Cannot Follow the Standard Cycle

Starting in 2013, I began to work in and around information communication technology being used during emergency response scenarios. I think my first paper was called, “Run Amok: Group Crowd Participation in Identifying the Bomb and Bomber from the Boston Marathon Bombing.”

The folks I worked with did and still focus heavily on how information retrieval, human-in-the-loop machine learning, and artificial intelligence can be used during a response to disasters. While this work has been amazing, much of it follows the way that all technology is developed. Nearly all work on technology in disaster has been done without talking to practitioners or if they did, did not involve them in anything more than an advisory capacity.

The result (for me, 9 years in but for crisis informatics 15 years in) is that while we in the information sciences understand a lot, we still have some hurdles to overcome, namely:

Very few of the other disaster research spaces include technological concepts. This is neither surprising nor unwarranted because of the current crises in the social sciences.

For example, this call: “Just before the holidays, we announced a new special call for proposals for Tornado Ready Quick Response Research in the social, behavioral, and economic sciences…” There is no discussion of the technical sciences or data sciences and rarely are those mentioned in conjunction with the social science calls despite much of the iSchools being made up of social scientists who left the social sciences.

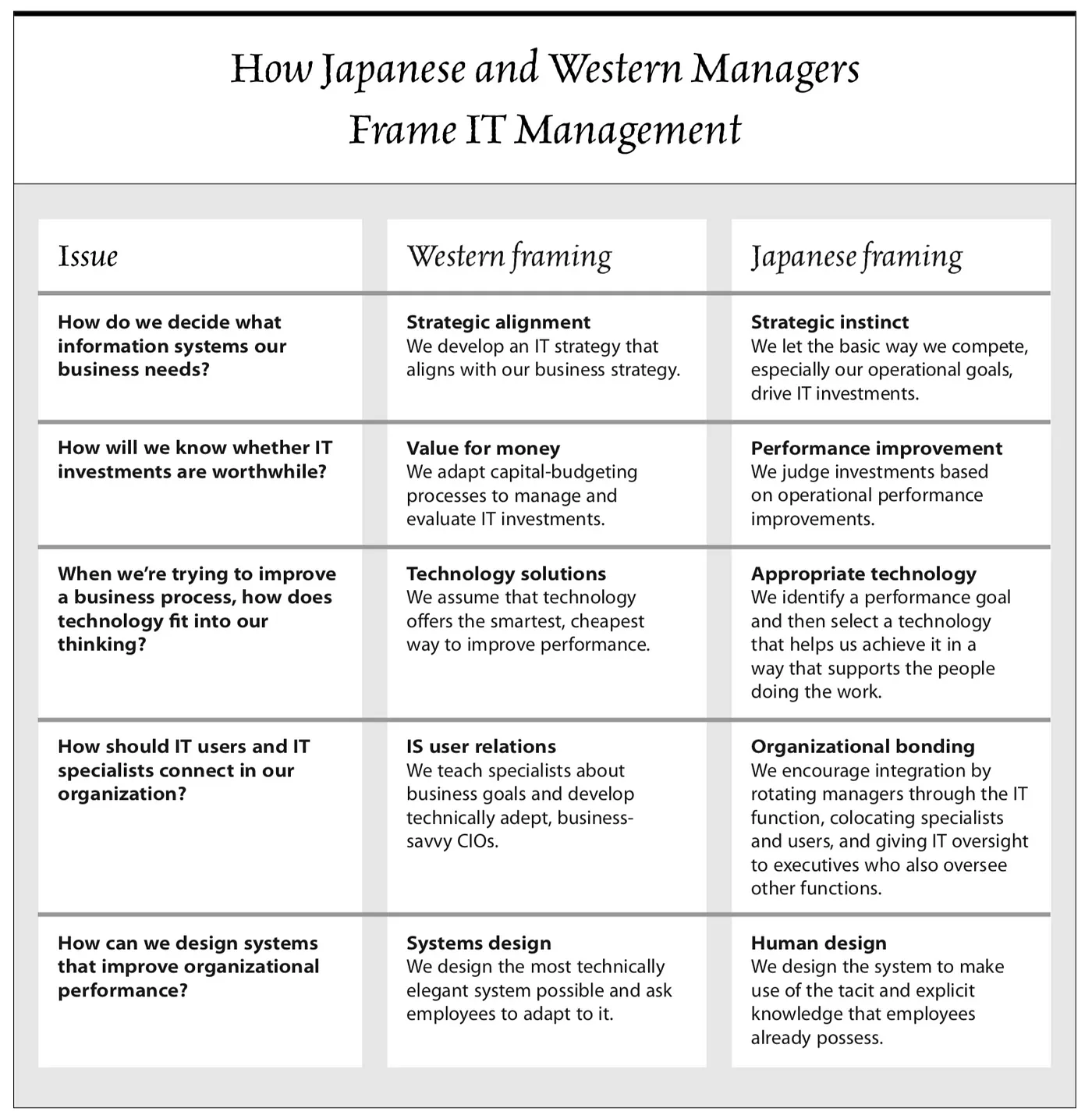

The technical spaces often have the wrong mindset for emergency management and by the wrong mindset, I refer to this reading. It notes that managers in the United States have a variety of complaints about technology adaptation.

They say that (copied from the PDF):

■ IT investments are unrelated to business strategy.

■ Payoff from IT investments is inadequate.

■ There’s too much “technology for technology’s sake.”

■ Relations between IT users and IT specialists are poor.

■ System designers do not consider users’ preferences and work habits.

Much of this can be seen more explicitly in a table in this reading. See below:

From, “The Right Mindset” which can be found: here.

So from this we can say that the technological sciences in the US are pushing tech without understanding the industry it is meant to be for. Or more directly, we can say that the tech does not have adequate ROI, nor increases in efficacy or efficiency. And that the technical spaces do not talk to those who are investing and do not consider them, their practice, or existing praxis.

Yet, there is a need for the fields in and around emergency management, including the social sciences, to begin to contend with the world that the industries in and around information communication technology has wrought. At this point, nearly everyone has a mobile rectangle that controls portions of their lives or at least connections to portions of their lives. And, for the most part, this was done without any forethought about their use within disaster because humans are the cause of all disasters and information communication technology has done this very quickly.

And so regardless of whether or not emergency management doesn’t use technology, the modern consumer uses so many apps, technologies, and devices that the mainstay of emergency management — the telephone — no longer has a place within the current methods and mediums of communication. This simple fact alone has caused innumerable issues for response efforts.

For example, during the Haiti Earthquake response, social media was overwhelmed with posts in, around, and about the earthquake that social media services like Twitter could not keep up. This caused supply chains to get inundated with an absolutely huge amount of donated, useless goods. During the Boston Marathon Bombing response, web communities like Reddit and 4Chan as well as hacktivist organizations like Anonymous and lulzsec caused investigators to move at wreckless speeds, causing the death of a security guard and one of the brothers responsible for the bombing. During Hurricane Sandy, misinformation about the event ran rampant with news media sometimes repeating incorrect information. And at the moment, the misinformation approaches that began during these events have formed the basis of modern issues in and surrounding purposeful misinformation and disinformation.

So regardless of what emergency management prefers, the modern consumer has been usurped by technologists and emergency management must contend with the impact on the efficacy and efficiency on their work.

This has taken the form of relying more and more on ad hoc communities like the Cajun Navy, Team Rubicon, and others like them. In essence, technology has moved too quickly yet is far too fragile to incorporate into emergency management properly. Yet, because of the way we consider technology the rhetoric around this is relatively toxic. For example, over the course of my career i’ve heard these 3 statements repeated constantly:

- Emergency management is just backwards.

- Emergency management is afraid of technology.

- Emergency management has to technical literacy.

Now, it should be noted that there are some aspects of information communication technologies that could be integrated easily. Databases, crowdsourcing platforms, and all manner of collaboration platforms could work well; however, because of everything from training to pedagogy and more, it just can’t be.

But the statements above are related to how technology was introduced to the english language. In addition, it is related to its attachment to data, communication, and shifting cultural norms around friend networks, social media, and advertising. Essentially, if tech use then more advanced. If no tech use, backward and old. Old and backward equals bad.

Yet, this is the wrong mindset for technology in general BUT ESPECIALLY for emergency management. This is true for 3 important reasons:

- Technology will not be reliable when a natural hazard descends onto a municipality (this is despite its predictable appearance because humans are why disasters occur and technology is the most fragile aspect of human-created technology yet).

- Training for Emergency Management is piecemeal because the industry is still relatively new and not fully realized. As such, no training for technology and its relationship to the central framework to emergency management — the incident command system (ICS) and the National Incident Command System (NIMS) — do not contain training or even approaches for integrating these systems to responses.

- Above from the “Right Mindset” reading, we noted that:

■ Relations between IT users and IT specialists are poor.

■ System designers do not consider users’ preferences and work habits.

And because of the existence of the above, “the IT office” is often not fully integrated, trusted, or imbued with administrative teeth that can force emergency management practitioners to learn certain things. This has factored heavily into response efforts recently.

In all, this leads to a lot of vulnerability created by the technical sciences that needs to be triaged by an industry that doesn’t have the capability to do anything about it. This is so complete a disconnection that not even academics can work together around the issues.

The normal behavior around this is to point fingers at the industry that doesn’t have the capability to do anything about it; however, the vulnerabilities created by tech belong to the tech companies alone and the ethical thing here is for the technology companies to seek to augment existing, normal practice in emergency management instead of creating tech for technology’s sake.

In doing so, we can foster a new, more stable and technically capable emergency management. And along the way technology will be made more resilient because it will need to be to be attached to emergency management practice.