Games as Summary or The Missing Mass of Games Doesn’t Have to Be Impermeable

In my formative years as a student in sociology (2004–12), I was pushed into the study of games by my mentors. They felt that because of books like Barbie to Mortal Kombat, My Life as a Night Elf Priest, and My Tiny Life that the study of games, of internet culture, would become a formative aspect of sociology moving forward. At the time, sociologists were increasingly interested in what people were doing online and compared to the way that Sociology had partially helped to demonize arcades, I was happy to see that their interest in these newly spreading online subcultures was not similarly constructed.

Yet, as I read the research I could find and attempted to write about what I was observing, I found myself increasingly interested in not only the material objects that surrounded games, but everything inside the playground or magic circle. From the electricity to the hardware, from the code embedded within the media to the medium itself, there were infinite microcosms to study and yet, all I had access to as a Sociology were people and this gate was policed heavily. My first attempts to write about games were not only rejected, but violently so. I was reminded of a quote from Simmel who said:

If one compares our culture with that of a hundred years ago, then one may surely say — subject to many individual exceptions — that the things that determine and surround our lives such as tools, means of transport, the products of science, technology and art, are extremely refined. Yet individual culture, at least in the higher strata, has not progressed at all to the same extent; indeed, it has even frequently declined. — George Simmel: On Culture

As this was the general composition of my reviews. “Technology doesn’t matter to culture.” Yet, since that time it has become increasingly difficult to make this argument. In fact, much of society is beginning to be mediated by technology.

At the time, I felt that maybe I could do what sociology wanted. Sure, people could be representations within the games. Sure, people could be fans, makers, reviewers, journalists, salespeople, and programmers. Sure, people could be on box art, in commercials, portrayed plot points, and customized as avatars; however, I kept coming back to the intersection. The most interesting aspect of games was the intersection of what made them work, the way they were created, how they ran, how they changed over time in concurrence with the people and objects within each of those contexts.

The code that made the game work, the mechanics and art created to foster immersion in the playground, the processor and the limitations its speed placed on designers, the hardware and its constant tension of upgrading, patches that shifted play completely, the room games were played in, the communication tools used to mediate communication between players and designers, hacks, addons, and even the media itself were all missing.

I was even more frustrated that in studying the people of games or the game as a text, that much of the object of inquiry was missing. And within what was missing was the history of all games that led up to this moment, this text, this product of inquiry. And within that frustration was an additional truth in that I had no methodological tools through which to access everything at once.

As a result, I began to learn how programming languages worked, but again, I was only able to access those languages currently in use. Languages like C, C++, C#, Java, Action Script, Python, and other languages like those. As I began to dig through discussions of these languages, I found myself mired in things like “design,” “user studies,” and “human computer interaction.” Each of these fields did the same thing as sociology’s methods but from the inverse. Only the software, hardware, and affordances really mattered. While users were often called out, these were typically switches between 0 did not accept design and 1 did accept design. On occasion there were calls to a 2 or “did something unexpected.”

And so attempting to do only inquiry about humans resulted in seeking new tools that fostered inquiry into technical objects sans humans. I attempted to engage the digital humanities in seeking new methods but again, found that the issues from social science and computer science were replicated within the digital humanities. And so the fix, the way I sought to expand my methods of inquiry were again thwarted.

It was here that I began to expand and find new allies. In this case, history was a reasonable next step, as was creating a Frankenstein.

I began to look backward to see if perhaps historical methods could help me find a way to unite these things. I started with 4 distinct spots:

- “The Turk” or the chess playing automaton that wasn’t really automated.

- “The Machine Stops” from E. M. Forster, a short story about a culture dependent on machines from the era of Sociology’s golden age (early 1900s) where it consistently negated the impact of non-human objects.

- The history of Dungeons and Dragons. This game represents a different / alternative history to that which became the computer. It also serves as a way to foster play with computers though much of that is buried in those spaces methods cannot access.

- Robinson Crusoe and Friday, the Other Island. If Crusoe was indeed the birthplace of what a modern person was meant to be like, perhaps this text could offer me insights. Additionally, the satirical account Friday, the Other Island, provided a useful dialectic to engage.

In each of these cases, I was grasping at straws for a way to understand the socio-technical system by way of pushing for both socio- and -technical to be balanced in their representation. I knew that games were a useful space of inquiry because Chess and its automation (Turk is an example of this (even if it was fake) but also Draughts/Checkers in some ways) was important to the development of computers while the history of Dungeons and Dragons allowed me to unite war, computation, play, and shifts in what we called upon to prove things.

I wrote about the history of Dungeons and Dragons as an endpoint for development that occurred throughout the 19th century. This allowed me to understand what Clausewitz meant when he criticized the war game stating it separated logic and emotion and would lead to issues in the future. “The Machine Stops” reflected those woes as the technologies coming out of the first World War provided ample inspiration for Forster to see what would inevitably occur.

Exploring history, exploring methods, and now having been trained as a technologist, a social scientist, and an amateur historian mostly just left me confused about what to do next. And this was a bad time to be confused as I was heading in to writing my dissertation. I knew I wanted to somehow work this content in. At the end of my rope, I had a realization.

It was actually a combination of 1,3, and 4 that helped me realize that I was not asking the right question. In essence, I wanted to find a method that allowed me to engage assemblages of humans and non-humans simultaneously. Yet, if technology is made by people to do something people need, then a networked way of understanding data is something that needs to be made manifest. While Actor-Network Theory was an attempt to do just that, ANT has been bogged down in the politics of attempting to reconfigure how the social sciences understand power.

As a result, ANT wasn’t a useful construct to immerse myself in. However, its tenets and basic premise provide useful building blocks for augmenting existing methods. For example, a network made of associations could act as a type of measurement, pre-defining actors could be a way to contextualize association, and summarizing them within a given space could provide useful data needed for the creation of products. I just needed something like an A/B test to consider when it occurred to me that if I took an activity like playing a game and compared that activity when a computer was mediating the game, then I could glimpse the impact of computation on the formation of a network in real time.

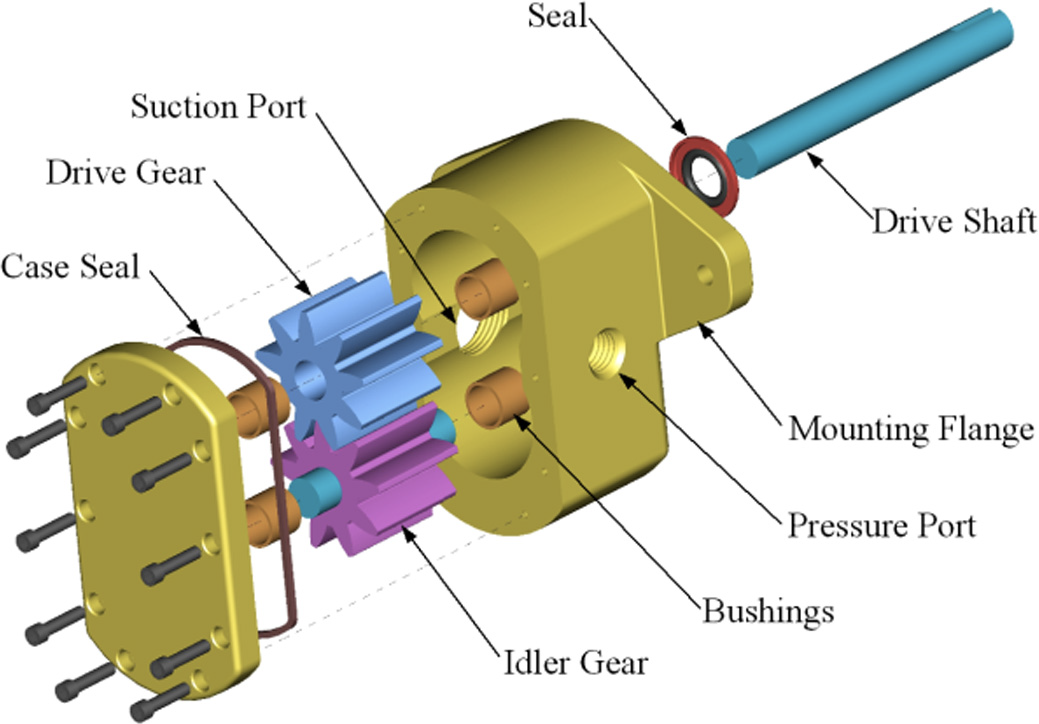

And by network, I mean that everything at the table, everything would need to be cataloged and evaluated according to the associations it had over the course of the game. In doing this, I could watch multiple networks form, persist, and dissolve. I could essentially watch players enter a magic circle, measure what portions of the magic circle were used by the players, and see the consequences of automating play by the processor. In essence, I wanted to consider playing a game something that looked like:

An exploded diagram of a gear pump.

And it worked! When play occurs, every piece within the magic circle becomes part of an assemblage, a network, that forms, persists, and dissolves in similar ways each time it is engaged. The differences (compared to a mechanical object) are essentially ways that intended design didn’t quite work or perhaps could be considered in future work.

While I won’t regurgitate my dissertation, the data and analysis from it essentially showed that computation doesn’t really impact sociality at the table, it lowers the cognitive load of the activity thus affording them the surplus energy to attend to other networks with other tools.

In essence, automating play, or perhaps digital play in general, lowers cognitive load and all we have left to contend with is psychological measures like flow, immersion, addiction, and other forms of keeping players glued to their screen.

I’ve recently written an invited paper about Association Mapping that is more tightly coupled to games and i hope to do more data collection in the future.