Are Fantasy Consoles a Better Gateway to Learning How to Program? Learning Programming with PICO-8

Published:

Fantasy Consoles are self-contained video game development environments so incredibly constrained that users have no choice but to learn how programming works.

I was once told that programming is the act of shifting around the limitations of resources, language, talent, or knowledge to provide a vehicle for users to do the same. I have thought about this a lot as I have begun to teach introductory programming and information processing. Teaching programming to those who are curious but apprehensive of actually doing it is perhaps one of the most difficult and consumptive challenges I have ever faced. I love it.

A few years ago, I inherited a game design program and found myself suddenly teaching everything from introductory courses on using Unity to the principles of game design. One of the things that struck me was just how difficult it was for students to learn two seemingly similar yet exceedingly disparate skills — programming games and designing games.

For the later, there are tools to design games that take the pressure of programming and try to sweep it under a rug. However, these tools still require an excess of programmatic thinking beyond anything most people will know. For programming, there are endless tutorials and endless approaches that force students to dig deeply into the act of programming. Much like that of invisible algorithmic biases or the lack of sociological imagination in computer scientists, game designers seem to fall into the same categories — designers or programmers. This is where I have tried to situate myself as an information scientist and scientist of the socio-technical: inside the spaces on a line between these two asymptotic curves.

What I want for an introductory programming class is a product that gets as close to intersecting with these two spheres as possible. This product needs to be able to do the following things:

Be contained inside of a small, lightweight, easy to understand piece of software.

Contain a simple, yet comprehensive interface .

Be welcoming to newcomers and more practiced programmers.

Be easy to use yet difficult to master with these two concepts codified and gamified.

Be reactive and display progress immediately without lengthy compile times.

There are several products that approach this type of environment but I want to focus on 2 specifically. Originally, I flirted with the processing programming language. This language is really quite amazing in a way that turtles are amazing. It is self-contained inside of a nicely designed piece of software. It also has some amazing community-oriented websites. There are also some incredibly beautiful visualizations that have used processing. It is small, lightweight, reactive, and is built around the idea of education with tie-ins to multiple languages such as Java and Python. It is an educational tool that can be used to jump into those languages.

But yet, processing, the way it is built, the way it is documented, and the way the community functions resembles expert-level programmer-communities. While a teacher or mentor can help walk interested and curious people through the language, the community, the tools, the books, and everything else it stands in complete resemblance of the very thing that keeps interested new programmers from taking the plunge. Finally, while processing is neat for visualizing concepts in programming, it is meant to produce programs, produce visualizations, and more. In essence, it is not limited enough to aid new programmers.

Python, Java, Javascript, even HTML and CSS all provide these same hurdles and this same issues of being, “out of balance.” We can produce programmers quickly but these programmers will rarely have the complete set of skills to actually help balance the equation created when computation developed over the course of the two World Wars. So I set out to re-consider a new approach and came upon a set of products that seem to exist within the factors I outlined above — they are called Fantasy Consoles.

What is a fantasy console?

Fantasy Consoles are self-contained video game hardware in the vein of the current retro-craze in video gaming. They are attempts to re-create the artificial limitations of video games from their early days. These self-contained programs are often built around extremely limited spaces of development. They do not allow programmers to expend the endless resources of modern computers, they allow for skim programs, and while they use modern programming languages, they are often stripped of a number of functions. Each of these fantasy consoles contain limitations that are meant to foster a sense of exploration and critical thinking about design, programming code, and how they fit together.

A small, yet powerful slinky from sprite to finished product

A small, yet powerful slinky from sprite to finished product

Over the summer, I have been experimenting and learning a little bit about many of the different consoles that are out there. Of the different fantasy consoles i’ve seen, the one that has been the most well-considered for new programmers seems to be PICO-8.

You can see it in gif above. Note that this gif is generated by the software itself.

PICO-8 and Education

After looking around trying to find something that met my initial grouping of 5 criteria, I started to dig a bit deeper into PICO-8. I found that my desires for a neat, interesting place to develop programming skills might be contained within the PICO-8 software.

Here is where it stood out.

On being small, lightweight, easy to understand

PICO-8 installed requires 10mb of space. It uses a limited form of lua which requires a very small amount of memory. All of the space limitations are known values. For example, PICO-8 is limited to:

a 128 x 128 pixel screen with 16 colors.

carts that can hold 15,360 bytes of compressed code with a maximum of 65,536 characters.

carts that reserve 12,544 bytes for graphics (8x8 sprites / blocks) and 4,608 bytes for sound but these can also be used for other purposes.

a maximum of 256 sprites though these can be sacrificed for more map space.

and a small, reserved and inaccessible amount of space in each cart for the lua interpreter.

All of this is contained inside of a 10mb piece of software that costs just $15.00.

On being a simple, yet comprehensive interface

The user interface consists of just 5 areas and a command line. Each of these do something specific for users to engage. Let’s take a walk through each.

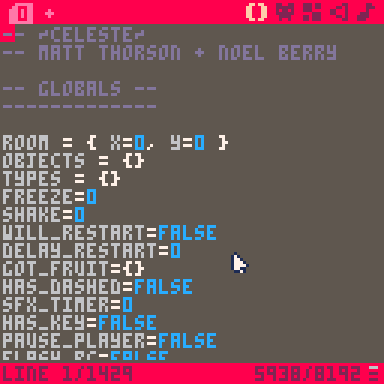

The command line

The command line

This is the command line as it looks after booting up the console. Here, users can enter commands to run files, import carts from the clipboard, or a number of other commands. One of these is SPLORE which access a number of demos for new users.

SPLORE is constantly updated so users can see new games consistently.

SPLORE is constantly updated so users can see new games consistently.

*The SPLORE menu **is a tiny graphic interface that let’s you look at various demo *cartridges for PICO-8 as well as a number of recent uploads to the PICO-8 community. This tiny menu will download cartridges to your computer allowing whoever downloaded them to look at each of the interface screens to see how they’ve done something. As it stands, each cartridge is a tiny text-file with the file extension “.p8”. While all editing can occur within PICO-8, they can also be edited by any program that can deal with text files. There is also a neat extension for Sublime that mimics the code editor of PICO-8.

From the command line, if users hit escape on their keyboard, they enter into a new user-interface.

The Development Interface for PICO-8

The user interface for PICO-8 is where all of the design occurs. Not only can you manipulate any game’s code from this interface, you can also load PICO-8 on certain hardware and program on the go. For example, the Pocket Chip is a lightweight, hand-held system that can run PICO-8. If you have to go to work, go to class, or go anywhere you can take it with you.

The user interface contains the following screens:

The Code Editor

The Code Editor

The Code Editor is for basic text but it will stylize commands as they are recognized. Anything here can be executed immediately at the command line..

Any errors will interrupt the program. The resulting error will be interpreted the line where the error first occurs will be pointed to.

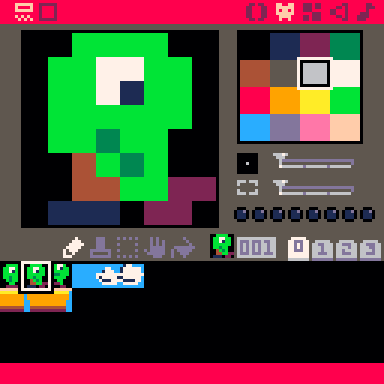

The Sprite Editor

The Sprite Editor

The Sprite editor is as straight forward as they can be. Each sprite is assigned a number with an additional set of flags for each sprite allowing for complex interactivity to occur should the user desire it.

For animating sprites, they simply need to be drawn in each successive sprite area and run through with a number of if statements.

The Map Editor

The Map Editor

The map editor allows for folks creating games that use maps to draw them as needed. The use of flags for sprites allow for programming-interested folks to use each sprite in different ways.

The picture to the left is one block of the map. Each of the blocks can be accessed here which allows for multiple levels in a game.

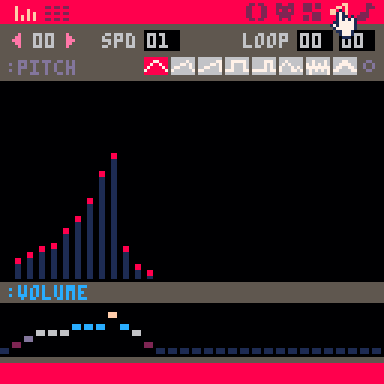

The Sound Effects Editor

The Sound Effects Editor

The sound effects editor allows for a number of different sound effects to be created in-house and ready to use in-game.

The editor uses different methods of generating noise that users can play around with easily until the sound effect sounds like what they want it to be. Each can be called upon by number.

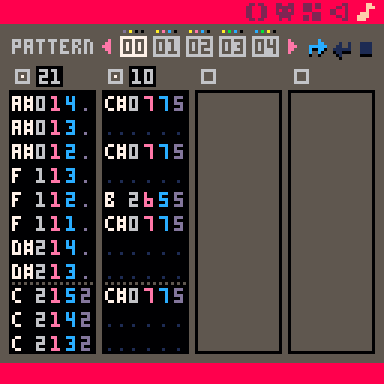

The Music Editor

The Music Editor

The music editor allows for patterns of notes to be repeated. There is room for 64 patterns each of which has 32 different notes that are possible.

Each of the individual notes are constructed around a standard music keyboard and can each be controlled as needed. Interestingly, there is not enough space for classic 8-bit music.

Each of these self-contained spaces allow users to not only engage in the act of programming, but also engage with the comprehensive aspect of designing a full-fledged product. As far as the requirement notes, this is an essential component of keeping programming and design in the same space.

Welcoming to newcomers and more practiced programmers.

Anyone new to programming is often shown integrated-development environments or specialized software like Jupyter Notebook. As they learn about how to program, they will get used to these software. Once this is done, they will inevitably have to learn other ways of doing things. Command Line Interfaces, the relationship of dependencies to programs, folder structures, and all the rest.

The nice part about PICO-8 is that it contains all of these things inside of one package. From SPLORE, you can look at all sorts of cartridges, you can look at their code, their sprites, their music. You can run them, you can even edit them as every PICO-8 cartridge is open sourced. Additionally, if a user types, “FOLDER” into the command line, it will open up the PICO-8 cartridge folder. Users can then explore the files themselves.

Additionally, since this is a text-editor, the relationship between the IDE and eventual text-editor norms for languages like lua are similarly replicated. All in all, this aspect of PICO-8 is one of my favorites.

Finally, there is a simply amazing user-community for PICO-8 but this will be explored below.

On being easy to use yet difficult to master as a feature of the program.

Because this software is associated with video games, there are endless tutorials, endless examples for users to pull from. There are also any number of game jams, coding boot camps, and code cleanups to consider. Users, especially new users, can be looking at the code, sprites, and music that makes up games within seconds of installation. Similarly, users can “Hello World” quickly and keep building on it from there.

In fact, there are more than a few cartridges out there that build on the concept of “Hello World” to teach about the most frustrating aspect of video game development — the game loop. One of my favorite series thus far is from the Lazy Devs (seen below).

Finally, each cartridge allows for users to keep expanding their ideas without care for memory consequences. That is, until the artificial limit is hit. This feature of PICO-8 is perhaps the most useful. One aspect of programming that is often either over- or under-discussed is the availability of memory. Carts can hold 15,360 bytes of compressed code with a maximum of 65,536 characters.

This limit seems limitless for new users but as they learn more about the ways that games work, they will continually make longer and longer programs until they suddenly are forced to start to condense or optimize their code. At certain points, these limitations will force game designers to re-consider their games. Perhaps this feature or that is simply too much.

On being reactive with immediate feedback

Finally, reactive with immediate feedback is an essential component. For folks who are learning interpreted languages, this is something that occurs quite a bit but typically this is reserved for text-based concepts. I can do something like visualize a for-loop in python with the Python Tutor but this does not really provide me with neat looking examples.

With PICO-8, I can draw squares and rectangles and watch as they move around the screen with variables in much the same way as processing. Additionally, I can also quickly upload my carts as they stand to the PICO-8 community so that they can be shared far and wide. Each cart exists in its own self-contained webpage. For example, the popular Celeste is available at: Celeste Good level design. Some of these strawberries are really interesting. I also liked how you teach which buttons are…www.lexaloffle.com

and each aspect of the game can be found within the interface there. Additional features for comments, allow users to share their carts with friends and co-designers to examine the game within a browser that allows for others to share, examine the code, and actually play.

I am excited about the world of the fantasy console and I am super anxious to start to try and use it to teach the basics of programming and how that programming relates to objects within a design. While on first blush it seems to be a piece of software that lends itself to teaching programming,

the culture surrounding programming,

the expectations of users creating games,

and the “trendiness” of a retro-oriented re-interpretation of the hardware limitations that fostered truly unique and memorable video games

all might lend themselves to truncating much of the possibility of fantasy consoles. Not being able to immediately make the games that “new designers” play every day can be disheartening. To them, I often point to this great bit from Ira Glass but often to little effect.

There is also pedagogical aspects of this style of software for an introduction to programming. Instead of a limited affordance IDE that attempts to bridge users used to software like microsoft word and proprietary text-files for interpreters or compilers, the act of programming is itself limited. Next, working with a piece of software like this might also not actually foster a sense of what a program actually does. The connection between a .p8 file and the PICO-8 software might never actually become an, “a-ha!” moment.

From a few reports i’ve seen on using PICO-8 in class, the way that PICO-8 presents itself seems partially hinder the act of learning how programming works. Or, at best, it takes those with a modicum of programming abilities and frustrates them as they attempt to use what they know inside of a new area that is too limited to be useful. The impact of these limitations on learning and fostering the idea of a balanced programmer is something that is in need of further study.

Along those lines, I have been slowly piecing together a course on introductory programming and design using PICO-8 that will be running for the first time this semester. It is of course no where near ready but I am anxious to begin to edit it, add to it, and make it more accessible for students. Seeing what works for them, what they dislike, and what they wish they could know as they work through the content will no doubt allow me to start to understand if what I see as a better path to learning a more balanced approach to engaging a computer at the programmatic level is actually viable.