First Steps with PICO-8

Published:

What is code? Why do we write it in PICO-8? What does that mean?

Before getting there, some context

One semester when I was new to teaching, I was asked at the last minute to teach an introductory HTML/CSS course for graphic designers. While the content of the course was set, I approached the course with an expectation that students would know or at least know how to look up 2 specific things. First, I expected students would know the basics of how the Internet worked and second, I expected that students would know what HTML and CSS files were and were for. How wrong I was is the basis of this piece which is meant for an, “aside” in a course i’m currently writing.

Over the years, I have discussed this disaster with others. The strongest point I’ve seen is one that a mentor made who suggested that in basic programming, we often begin with tiny steps like “Hello World” or “Calculate 2+2.” After that hand-shake and brief intro, students are then slowly introduced all manner of concepts: variables, arrays, IF, Functions, etc. It isn’t perfect but organizations like software carpentry, we can see efforts to stabilize it, routinize it, make it more friendly.

Each step of learning how to program is more complex but always (at least hopefully always) connected to the previous content in both context and practice. In HTML/CSS courses, the curriculum often demands more than, “hello world.” In fact, as I sought answers to how to make that course make more sense, the project I saw the most (in an intro course) was: “Make a portfolio using your knowledge of graphic design.” Students in both sets though are not taught how to write, where to write, or why we write HTML/CSS. Yet, in those courses we tend to grade implementation and design. There’s a tremendous gap here and I believe it carries over to video games as well.

For example, a lot of students I have met seem to fall under this spell, faculty do as well. “You have been playing games that cost billions to make, let’s learn how to make those!” This is without providing knowledge of computers, programming, programming teams, or how all of those interact. Perhaps this is a bit hyperbolic but it’s a lot more common than it should be. I have been thinking more about the industry that was created throughout the course of my childhood. Video games began with little memory, little capability, and little more than a collection of dots drawn on a screen just as a beam of light was shot across a screen. If we’re teaching design, it should begin here.

This has lead to me to consider learning to program as an historical process. In the world of video games and video gaming, this process should not be through Unity or Unreal Engine. It should not be through learning any of the C languages, action script, or even the maker programs. It should be done in a space that resembles a world where the first video games were made.

But we can never go back to that space. Instead, we have to rely on new interpretations of the past. We have to consider something like Shovel Night or any of the Retro-games out there. As this article notes: “What if development of the NES never stopped?” Or for that matter, what if the Atari, the Amiga, the Commodore 64, or the Intellivision were still active consoles? Would we teach to make games with the AAA experiences we have now or would we instead begin with these early consoles? This is where PICO-8 sits for me. It is a perfect vehicle to start a ride into design that does not skip history, it celebrates it.

It’s great to think about starting with PICO-8 as a way to talk about the history of games in both application and practice, but there’s still more to consider. We know a lot more now about educating programmers and designers than we ever have.

I think still of that HTML/CSS course. I want to learn from the mistakes of that course. From there, and from educators like Greg Wilson, I think it is safe to say that there initial barriers to learning how to program. These are very necessary pieces of knowledge that no one ever actually tells anyone. I’d suggest that there are two questions that could cover it.

What is code?

Where does coding occur and why?

What is code?

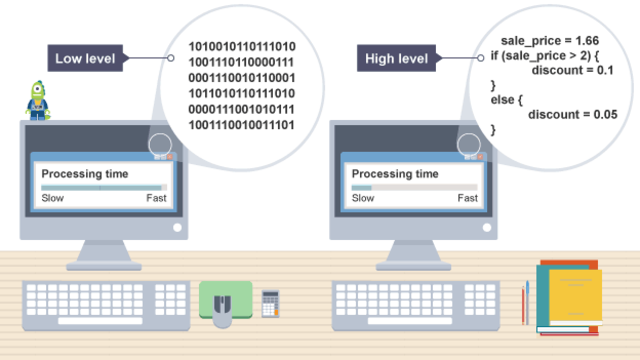

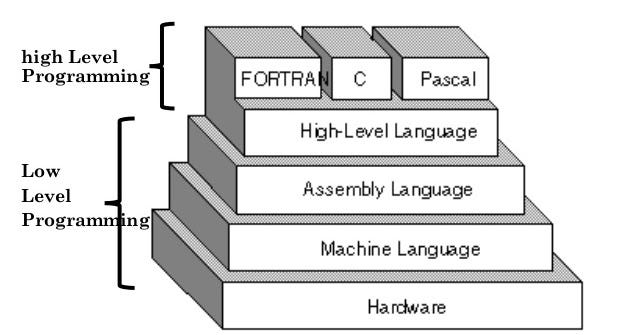

The easiest way to describe computer code is through the concept of levels. At the very bottom level there is the language of the machine. We most often see this represented as a series of 1’s and 0’s. These 1’s and 0’s are in patterns so that the machines that make up the computer perform certain activities. There are languages above this that are still considered low level but this is the basics of it.

Above the low level languages are, of course, high level languages. These languages look like those that we see all the time on tv shows and on accident when a program fails or when we hit certain buttons on accident. The picture below should help to represent those things.

There is a sub-question to the above though, “how does it get from the high level to the lower levels?” Well, as the code moves from high to low, it is interpreted and translated then sent on to the next level until it gets to the machine level and is carried out. This is related to the second question.

Where does coding occur and why?

This will begin with a lengthy, “Why” first.

At the high level, languages exist that are formalized and structured by committee that is enforced by “releases.” This is why you’ll hear about “HTML 5” or “Python 3.7.” Those numbers mark that a language has changed and these languages are ones you might have heard of before like the C languages (C, C+, C#, etc), Python, Processing, Java, or even the markup languages like HTML and CSS. These are the language that we “program” in as they contain commands written in languages meant for humans to learn, to write, and to design with. These languages are created in such a way that there is something interpreting and translating the code from what humans create to what machines need to function. We’ll talk more about this later. But first, why do we create that “high level” code?

We create code inside of a program. In our case, we’ll be working with PICO-8. This program is where we will create code because it contains two specific things: 1). an unformatted space to write in, and 2). a way to run the code. Code is almost always unformatted. This means that it contains only the letters, lines, and line breaks that is bereft of any formatting like bold, italics, or other concepts. You cannot write code in so-called, “rich text” programs.

This means that code cannot be created in Microsoft Word files or inside of a file on any word processor. These files have all sorts of extra data associated with them, data like font, text formatting, and other things like pictures. These are called, “rich text” files. You will be working in PICO-8 which creates unformatted text files with the extension, .p8.

While they are called, .p8, these files are also plain text files. (these are often noted as, “.txt”) These files contain only 2 things: line breaks and spacing. We will be using PICO-8 to create and run those files but you can also create them in programs like:

and as long as the file is called, “yourgamenamehere.p8” it can at least be loaded inside of PICO-8. But why is it called this? What does all this mean?

Well, let’s start from the above picture. At the very top are some programming languages. PICO-8’s language is a form of another programming language called LUA. It, like FORTRAN, C, and PASCAL are all high-level languages. You write programs in the language you need and then you run it through an interpreter or it is compiled. So what converts a language, or translates it, to the lower levels?

For PICO-8, the language you write, the commands, the .p8 files you write is interpreted and translated and sent toward machine language and eventually the hardware (eventually being nearly instantaneously). This means that the words and commands you write, once you hit run, are sent to an interpreter. The interpreter takes those commands and translates them into assembly language, and then so on and so forth down into the hardware. As that language is interpreted, you can see results. PICO-8 contains a translator, Lua’s interpreter, and so as your .p8 file is run, each line is sent to the translator and placed in memory if need be.

This is why computer code is so difficult at first. You need to know precisely (or at least mostly) how to write your code to get the result you want. Computer languages, especially machine languages, are rigid and very structured. None of these lines of codes can contain *any errors. *If they do, either the interpreter stops translating or compiling stops or you end up with an error. Sometimes the program works but “unpredictably.” But how often is code sent to the translator? This depends but in PICO-8, we know exactly how often.

In this class, you’ll hear about “LOOPS,” specifically the game loop. What this means is that you are sending a certain block of code (usually noted by the names: _init, _update, _draw) to the interpreter for every frame the game is sending. So when you hear the term 30FPS or 60FPS, it means that once every second, that block of code has been sent to the interpreter, translated, and run by the hardware 30 times or 60 times. As you’ll see in the rest of the course, because your object’s positions, color, or animation logic changes, the player sees a dynamic game in front of them. We’ll unpack this a lot more as the class continues.

So now you have some basics as well as some context from where those basics come from:

What is code? Well, it’s unformatted text in a file marked with an extension associated with the program you’re using to run it.

Where does coding occur and why? It occurs inside of PICO-8 which looks at .p8 files and interprets it, translating the code in the file to machine languages 30 or 60 times each second.